So here’s something. I received a link to the following article today (thanks cuz); a submission to the New York Times Draft blog for writers.

So here’s something. I received a link to the following article today (thanks cuz); a submission to the New York Times Draft blog for writers.

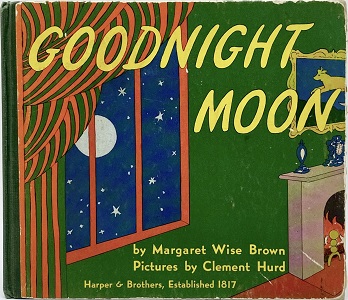

What Writers Can Learn From ‘Goodnight Moon’

Though I was certainly an English major, I’ve actually never, believe it or not, fully analysed an entire critique of Goodnight Moon before. And this piece, focused on writing technique, spoke to me as a writer – there are definitely interesting technique takeaways in there.

But today specifically, I took something else away too. It had actually already been on my mind. And that related to the perceived ‘innocence’ of children.

Here’s what the author, Aimee Bender, has to say about the way Goodnight Moon differs from other children’s books:

It works like a sonata of sorts, but, like a good version of the form, it does not follow a wholly predictable structure. Many children’s books do, particularly for this age, as kids love repetition and the books supply it. They often end as we expect, with a circling back to the start, and a fun twist. This is satisfying but it can be forgettable.

This had me circling back to what I, quite literally, woke up to this morning: my five-year-old son showing us a drawing he made of a boy, perhaps himself, choosing shelter during a rocket attack.

With everything going on lately – in the world, downed planes, civil wars, massacres, and at home, rockets, air strikes, terrorist kibbutz plots, collateral damage – I’ve been wondering lately how much innocence really is lost from children. How much innocence they have in the first place.

Are children as innocent as we assume, and if not, should we be pretending so?

Around the world, millions of children lose their innocence a lot earlier than say, middle class Western kids. And that includes plenty of American kids who are homeless, poor, hungry, and trapped in a devastating lifestyle.

How much innocence is there, really? Is it, say, a shelter of sorts, from an eventuality? Is it the lucky few who even get to experience the so-called innocence?

Is it our own regret at reaching the threshold of adulthood, passing through it, and forever exposing ourselves to the world we’ve actually been living in the whole time?

Back to Goodnight Moon. What always bugged me about it is that it’s not smooth. It’s not neat. The author lays out the room, and then goes on with the goodnight chant, which is perfectly natural, but the contents of the chant don’t match up. The pages aren’t parallel.

What a surprise, then, to find that there is a blank page with “Goodnight nobody” out of nowhere, sharing a spread with “Goodnight mush.” What a surprise, then, that the story does not end with the old lady whispering “hush” but goes out the window into the night.

Goodnight Moon feels like it should be a tidy tale. It’s not – it’s bumpy. What you expect doesn’t actually happen.

Perhaps that is a piece of children’s literature that speaks truth to children who are supposedly ‘innocent’ or blank slates. In fact, a little bit of a bumpy ride might feel natural to a small child who hasn’t yet neatly summed up the world as good vs evil.

There’s been talk lately about how much to expose to our young kids, how far to go to protect their ‘innocence.’ I’m just not sure how much of that is a construct of the safe situations we were lucky to grow up in. In which, eventually, we too lost our innocence.

Kids, even living on the safest terms, don’t exist in a vacuum. And I reckon they’ve figured out long before we think they do that life isn’t a Disney movie. So what should we have them think in times of stress? When things get ‘real’?

If it’s real for us, surely it’s real for them?

What do you think?

Whadya got: