Waiting on line to enter a session, I became totally consumed in fascination over the behavior of some of the other people in line. Of course I use the term line loosely. People queued up early, creating a mob scene within five minutes.

I couldn’t help but focus on a particular woman at the absolute front, pushing at the rope cord, snapping at the stubborn security guard, and even tattling people who seemed to be getting ahead and sneaking through a different door.

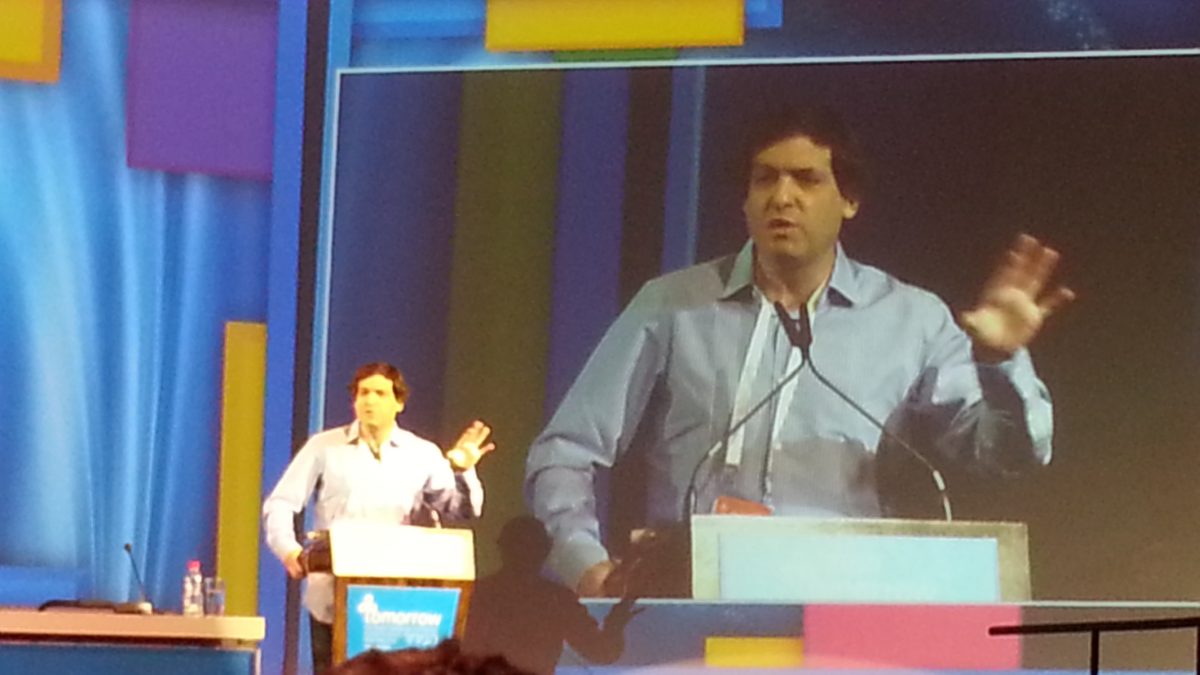

All that, and here we were waiting for a talk by renown professor of behavioral economics, Dan Ariely, who was to address dishonesty and our tendency to act dishonestly.

Here are my notes from his highly entertaining talk:

There was a troubling piece of research: two people in a room. We ask them to please talk to each other for ten minutes, introducing themselves. Ten minutes later we asked ‘did you lie in the last ten minutes?’ Everyone said no. When we played back a tape… turns out, on average, people lied 2-3 times in ten minutes.

We all lie from time to time… but we all generally think of ourselves as generally nice and honest people.

How do we rationalize this?

Well, even God lies: In the story where He tells Sarah that she will have a child with Abraham, she laughs – my husband is too old! God tells the same to Abraham, but tells a white lie in there – after all, it;s for shalom bayit!

How do we measure dishonesty?

Here is one method: We gave people a sheet of paper with 20 math problems – everyone could solve all the problems with enough timem but we only give five minutes. After, they are told they get a dollar for every coreect answer, and to tally them and then shred the paper. On average, people were given six dollars for siz correct answers.

What the testers knew is that on average, people were actually getting four right.

Is it a few people who lie a lot?

No. There are a lot of people who cheat a little bit. There were 35,000 people in that experiment!

And it’s not too far from real society: there are big cheaters, but only a few. There are more little cheaters, like us, so we can feel ok. However, the economic impact of all that small cheating is actually higher.

What do we stand to gain and lose – is it worthwhile?

We changed the experiment – offered different amounts of money per correct answer. As the price went up, the cheating didn’t get higher. It stayed the same.

Lots of people cheat just a little, regardless of the probability of being caught.

People try to balance two forces:

- we look in the mirror and want to see good people

- we want to benefit from cheating

Due to our flexible skill, we can do both – as long as we cheat a little bit.

What influences rationalization?

A biggie: ‘I’m not really hurting anybody.’

People download illegal music… but they won’t sneak from a restaraunt without paying; that’s something that they enjoyed and interacted with people throughout.

Another way: Like stealing 50 cents from the office petty cash vs stealing a pencil – no one feels bad for the pencil.

We are becoming a society that has multiple steps between us and the people were dealing with. money is becoming more abstract – we’re not just dealing with cash. As the distance between ourselves, other people and money concepts, grows – what kind of people are we becoming?

How could you decrease rationalization?

We experimented with people signing honor codes – gave them a chance to cheat – but saw no cheating whatsoever. Even though it was a meaningless document, and they knew that, it still worked.

What happens when people are given many chances to cheat over time?

People cheat a little bit and balance feeling good, and then at a certain point people switch, and start cheating all the time. We call this the: what the hell effect.

So why would people ever stop?

Experiment: give people the chance to ask for forgiveness, confess. Once they do, cheating goes down dramatically.

South Africa used this idea for their reconciliation period after apartheid. If people can have a chance to say they are sorry then people can move on and change.

What are the cultural implications?

Actually, Israelis cheat just like the Americans. Who cheat like the Italians, Chinese, Germans, English, Canadian, Colombian – all tested, all the same.

But dishonesty looks different in different places – how can it be the same?

The experiments are abstract and general and not embedded in any culture. They test the basic backbone of human culture. In that regard we’re all the same. But culture operates on top of it – it takes a domain – like illegal downloads, bribery, speeding – and tells you it’s ok to cheat. It matters per country, per domain.

My favorite part of Dan Ariely’s talk?

When a moderator came in and handed him a note he had 5 minutes left. Dan looks up and says, “but my clock here has 8.5!” he looks cheekily at us in the audience and says, “I’m going to take the bigger one because we’re talking about fudge factors and cheating.”

More #tomorrow13:

- #tomorrow13: Bill Clinton on Israel, peace, and how to change Us vs Them

- #tomorrow13: Guessing at tomorrow – health, terrorism, climate, economy, politics, and of course, Yair Lapid

- #tomorrow13: Dan Ariely on online dating & the ideal BMI to snag a man

- #tomorrow13: The missing demographic; the outsiders left further out

Whadya got: